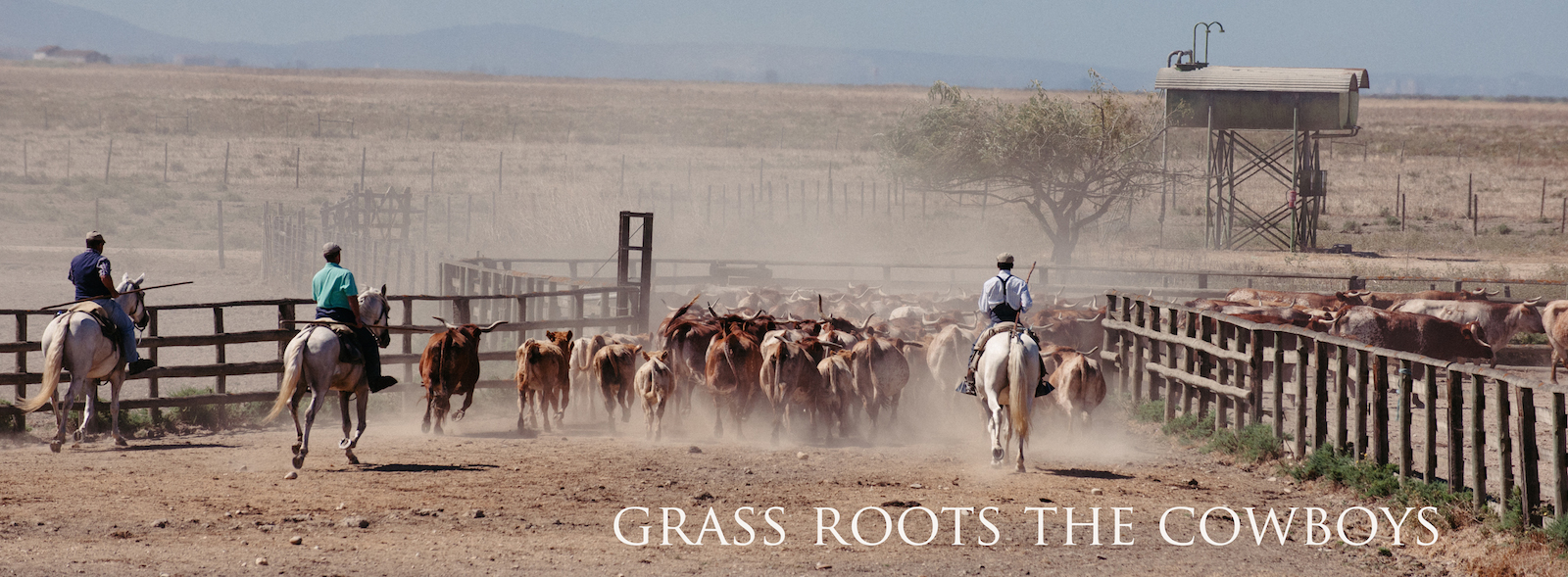

The cloud rolled towards us. With the rumbling sound of pounding hooves on the dry ground, they carried the dust onward, hiding in its dense billows. Then, like magic, the front riders appeared, bursting through, followed closely by the cows as they trotted into the corral. The rest of the Campino team brought up the rear.

In no time at all, the cows and calves were in a small pen, and they quickly separated the cows into the paddock and had the calves checked and marked, ready to go to a field on another farm. This was the sad part of the day, hearing the cows calling to their babies and trying to get back to them. Rodrigo told me this calling goes on for about a day and a half to two days, and then they are relaxed again. He admitted that he found this bit hard to watch, as well.

The superb skills of the Campinos are not found in books or taught in any courses. No DVD or YouTube videos exist that show how it is done. The skills are passed down from father to son, or form uncle to nephew. Currently, about 25 farms still employ Campinos—mostly in the Ribatejo region, and a few in the Alentejo. There is a lot to be admired about the lifestyle and work done by these often-overlooked men. They are excellent horsemen and have wonderful relationships with their horses. The horses are not kept in the luxurious conditions that many of our horses enjoy today, but I would say that they are happy and content with their lives. Clearly, they could almost work with the cattle by themselves; they are so in tune with the task and eager to do it.

The Roots of Working Equitation

The now international sport of ‘Working Equitation’—founded in Italy, Portugal, Spain & France—was developed with the idea of preserving traditional country riding, farm work, cultural traditions, and costumes and tack from each country. This sport is exciting to watch; the idea is to demonstrate the collaboration & trust between horse and rider. It´s a combination of flatwork (dressage) and ‘natural’ obstacles that reflect country riding activities, in addition to the use of garrocha (vava) to working with cattle. Working Equitation promotes good horsemanship and has been described as “functional dressage”, as the aim is to have a functional horse-rider relationship. It is a sport rapidly gaining popularity worldwide.

Read more about Working Equitation (WE)

Also read about Working Equitation – An Olympic Sport?

There are fairs and shows in the Ribatejo region where one can observe the Campinos demonstrating their skills. There are two in particular worth visiting: The Santarem Fair and the Campino Fair in Salvaterra. Both fairs will be announced on the LHF website with dates and details nearer to fair time. They are also seen at the International Lusitano Festival in Cascais, doing small displays and presenting horses during the Breeder presentations.

At all these fairs, they wear the traditional costumes—white shirt, green and red hat, red waistcoat, dark blue trousers, and white socks. The buttons down the sides of their trousers and on the waist coats are gold and shiny.

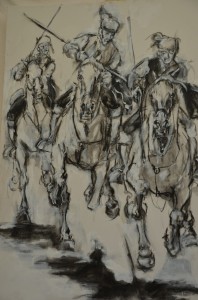

Sabine Marciniak is a painter in Portugal producing fabulous painting and ceramics of the Campinos, bulls and other traditions in Portugal check out her work on her facebook page

Lena Saugen and I would like to say a big thank you to Companhia das Lezírias; Rodrigo Pereira, Farm Director; Fernando, Campino/Farm Manager; and the whole Campino team for such an excellent day.

Editorial text – Teresa Burton Photography – Lena Saugen

another field.

another field.